Low foreign inflows supplemented to CAD woes

What is present account shortfall (CAD)?

The inflow of cash into the homeland and outflows from it are summarized in what is called the balance of payments (BoP). You could think of it as a balance sheet vis-à-vis the rest of the world. The BoP is broken down into two major components — the present account and the capital account.

The present account encompasses all inflows and outflows of a usual environment. Thus, exports of items and services, remittances received from Indians overseas, foreign visitors bringing cash into India and similar other pieces form part of the inflows or the borrowing edge of the present account. Conversely, imports, remittances by expatriates to their dwelling countries, Indians journeying overseas pattern part of the outflows or debit. When outflows exceed inflows, you have a present account shortfall. Of course, if inflows exceeded outflows, it would be a surplus.

The capital account agreements with longer-term flows, like borrowings, investments, aid by India to other nations or to India by other ones, and so on. The very wide standard is that any inflow or outflow that tends to necessitate future transactions (like borrowings being returned) will be part of the capital account. Here afresh, the distinction between outflows and inflows would be the capital account surplus — if inflows exceed outflows — or shortfall. If the capital surplus is not sufficient to cover CAD, the homeland will have to take cash out of its forex reserves to connection the distinction, thereby decreasing its reserves. If the capital account surplus is larger than CAD, the difference gets added to the reserves.

Why is CAD so important?

In effect, it is a measure of how much an finances is reliant on capital flows from overseas to help it rendezvous its present needs. Obviously, if this dependency is high, it is a signal of a problem. To see how high the dependency is, economists gaze not at the unconditional grade of CAD, but its grade in relative to the size of the finances, since a minute finances with, state, a CAD of $200 billion is apparently in a larger aperture than a large economy with the identical absolute grade. Hence, what is looked at is the CAD as percentage of GDP. In India’s case, this is now at about 4.8%, a significant increase from about 1.3% in 2007-08. What this means is that India’s demand for foreign currency, especially dollars, has gone up spectacularly in the last couple of years (mainly on account of oil and gold imports) while provide hasn’t rather kept pace (thanks to feeble exports).

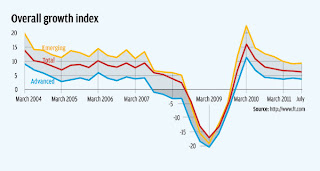

The widening CAD could have been financed by a heavy inflow of foreign investments — direct (FDI) and/or institutional (FII), but that hasn’t occurred either. Policy paralysis, political uncertainty, skidding developed output and a dwindling finances

(as apparent from a quarter-on-quarter fall in growth numbers) has turned off foreign investors, who now find they can get better comes back on their capital in another place in the world. This demand-supply mismatch of dollars is at the centre of the US currency evolving more costly.

How are US bonds connected to all this?

US treasury bonds are vitally devices floated by the US Federal Reserve (the American equivalent of the RBI) to borrow cash. All other things being equal, the status of the US as the world’s biggest finances and the dollar as a international reserve currency means that investors glimpse putting their cash in US bonds as arguably the most risk-free option. although, when US treasury bonds offer very reduced rates of interest, this benefit can be offset by other ones proposing significantly higher rates. In such a situation, portfolio investors, who roam the world looking for the best possible comes back, are more likely to invest elsewhere. appearing markets, encompassing India, are often the biggest gainers in such positions. When the US economy is doing well, the flows can turn around. This is what is occurrence as the US finances displays evident signs of retrieving after a extended urgent situation (starting late-2008).

What is the QE and why is its tapering glimpsed as a problem?

Following the 2008 urgent situation, the US Fed resorted to bond-buying as a means of increasing the finances. When the Fed buys up bonds, it is competently issuing more cash into the markets and therefore decreasing interest rates (since interest rate is vitally the cost of demand for cash, so when provide increases to rendezvous demand, interest rate arrives down — just as, state, the cost of onion will fall when provide in the market rises). This was named a ‘quantitative alleviating’ measure, therefore the QE. This made scrounging in the US cheaper and hence incentivized borrowers to invest (in housing or in their businesses). In June this year, Fed chief Ben Bernanke indicated that the QE process might be tapered off. That would suggest interest rates in the US climbing afresh. That, as we glimpsed previous, could lead to investors flocking to the US and dragging out of appearing markets, encompassing India.

No comments:

Post a Comment